I am happy to share a GitLab CI/CD video that is concise, technical and up-to-date. I have chosen this video as the best of several videos that I have recently watched.

At your convenience, we have added subtitles, a summary of the video and the transcription of the video. You can watch the video and get the summary by leaving details here below.

What you can learn from this video?

- How GitLab CI/CD works

- How to configure it in order to build pipelines that are tailored to your needs

- How to run CI pipelines (in this video it’s a Java-based application)

- How to configure runners (i.e. nodes) and how to run tests

Watch the Video (30 min.):

Need Help on Moving to GitLab CI/CD?

Contact us — we can help with:

- Building pipelines

- Switching from other tools such as Jenkins

- Training

- Setting up runners integrated with Kubernetes and using the cloud

- Creating customized reports and graphs based on GitLab API / Excel

- Integration with Terraform and similar infrastructures-as-code tools

- Integration with HashiCorp Vault and similar secrets management tools (e.g. Akeyelss Vault)

and more

Relevant Links:

- Our GitLab website

- Free-of-Charge Serverless Computing Using GitLab CI/CD

Transcription:

So here we’re in GitLab so GitLab CI is a it’s an integrated it’s scalable it’s flexible and it’s a self-service tool

it’s easy to set up maintain and and it requires little intervention from an admin and in order to perform those tasks that that you need for your project.

I’m gonna look at GitLab as GitLab is made up of two main parts: the GitLab CI YAML file which consider to be the brains

and the GitLab runner which is the body.

what I’m gonna do is start with the GitLab CI YAML file this is the pipeline definition file which specifies the stages jobs and

actions that we want to perform.

gitlab-ci.yml

As you can see this file is checked into our repository which provides a number of benefits: the file is versioned which means

pipeline changes can be tested in branches supporting any changes into your app code similarly if you need to go back to an old version of the the associate pipeline will be exactly how you left it for that particular release,

and because it’s under version control it’s easy to diff the file between versions for easy troubleshooting.

It also means that there are a large number of ways to work with this file so nearly all IDEs have direct integration with Git.

If not GitLab so you can use your favorite editor.

Classic command line of course is always possible as well as our

integrated GitLab built-in web-based editor that you can see here.

Let’s take a closer look at this file and we can see and see how we could

define the pipeline and integrate that

with a wide variety of tools.

So at the top of file we have a few defined global defaults:

a Docker image to run our command

then in this case the official Maven image.

Now this pipeline file: you’ll see that I’ll

probably use a lot of containers and

this doesn’t mean that GitLab CI is restricted to just using containerization.

We’ll talk a little bit more about the GitLab runner.

GitLab Runner

The runner can be installed on a bare-metal machine or a virtual machine (VM).

Just think that a containerization makes things a lot easier for folk in many cases.

You can see that we have a few environment variables, we have some cache settings

with a lot of folders to be persisted between jobs to increase our performance

and next what we’re gonna start doing is defining our stages and jobs and GitLab CI.

A pipeline is made up of a series of stages.

Each stage then contains one or more jobs, so there are no limitations on

how many jobs the single stage can have,

and so we see with that that

the stages keyword is going to define

the order the stages should execute

regardless of the order that you defined on the individual jobs.

So in this case our flow is going to be

build, test, generate docs, deploy and trigger.

When we start to define our jobs

or the actions that we want to perform, our first job is to build our library which we utilize Maven for.

You can see here we simply invoke Maven as we would as if we were running

in our own machine.

That is because the script you see here is actually just a bash script.

This provides a great amount of flexibility because you can

now automate anything you normally would do on your machine.

After we build our library we’re now going

to test it so our test stage includes …

This is just a demo so you

may have more complex or more have more

complexity to the different stages and

more jobs that you have within these, but

but for demo purposes it’s a

couple of simple steps, so test stage

includes two jobs, unit test and static

analysis with Code Climate, and we’re

going to leverage Maven again to run our

first test but will also include JaCoCo

to generate code coverage reports.

We then are going to output the coverage percentage into the build log, and the last step in this job

that takes our code coverage reports and persists them with GitLab’s

integrated artifact repository, so the result can be used by other jobs

or downloaded through the browser directly

How we do this? By simply just specifying the folders that we want to save.

While this is happening, we will also be running a static analysis with Code Climate.

Here we override the default image to utilize

the official Docker image,

and so we use that then to run Docker in Docker

to execute the Code Climate image

to analyze our source.

Once that is done we retrieve

our JSON and persist it as an artifact.

The doc stage is just simply generating

our Java Docs, again retaining them

as an artifact .

Release

So now that we’ve tests of our library we are able to release it.

We are going to use Maven again to publish our

library out to the package cloud server.

Now if you’re paying close attention (hopefully you are), you’ll see that we are

using a variable we did not define above.

That is because this is a credential token which should not be checked into

the repository. Instead we add this as a protected variable in our project’s

settings which only administrators can view.

So as an admin I can go over to Settings > CI/CD

I’ll just go to variables, and we can see

that we have that PACKAGECLOUD_TOKEN here.

It’s a hidden by default, and if I want to reveal that, I could reveal that.

If I want to, they can protect it I could do so If I want to choose a specific environment I can do

that here.

Next, our pages job, and

this is slightly unique and that this is

a special job that works in tandem with

GitLab Pages, which is our static site

hosting feature with pages.

Deploying a static site is really as

easy as create an artifact.

We do that here by specifying that

we will utilize artifacts

of our two jobs, unit tests and javadocs

This job then copies those into a single

directory structure and it persists it

as an artifact, so GitLab Pages will

then take this and deploy out to the

integrated hosting service providing

a very easy and automated way of

posting in our case our code coverage and documentation.

See that here.

No the prettiest UI but it’s still doing what we need it to do.

You can see the coverage,

you can see that being done here.

Finally we have our last stage, trigger.

For this last job our Java app is made

up of two components. This is a library

and a front-end service, which used it,

which is another project, and at this

point what we’ve done is we’ve confirmed

so actually at the trigger stage, at the

at the trigger point we’ve confirmed

that all of our tests pass prior to this,

which is a great start, but now what about

downstream projects that are utilizing this?

And this job kicks that off to what

we refer to as a cross project pipeline,

and so we take a stock Alpine image.

It’s all curled and used to trigger

the API web hook to start a new front-end

service pipeline in the other project,

confirming that downstream

projects are not negatively affected by

upstream changes, and it’s just pretty

simple, it’s very just easy as a few lines of YAML.

I’m gonna do that.

I know, it like we have a certain amount of time here

and I’m running through this

stuff and obviously always after

webinar is done I’m one happy to follow-up

but just base I’m keeping that just want

to make sure we get all the information

out to you as much as possible about CI/CD and in the 50 minutes we have allotted.

So as you can see,

this supports our larger goals

of GitLab, so it’s supporting the

scalability, it’s supporting flexibility,

it’s supporting self-service,

and so a developer, they can integrate with

any tool that they need.

Just a couple examples that we have just the YAML file

without having to worry about installing

plugins or involving administrators.

In most cases they can simply provide the

required container or VM to run

the script in or install their own runner

on a bare metal machine. I would associated

requirements, integrating with static

analysis and unit test

frameworks is just a few lines of code.

We also have a collection of templates

which can be used to help users get

started, and I will show you that over in

the repository, so if I were going to

create a new file. As soon as I just get

the .gitlab-ci.yml, which is already pre-populated here, you’ll see

that I have some templates that pop up here

and give me a drop-down menu, and

this makes things easier and faster just

as a jumping-off point for a lot of users.

Templates are in almost most

languages, and I could choose whatever

I’d like. I’ll just may be working on some

mobile app, specifically focus on Android.

Once I clicked on that it’s

going to give me some variables and some

basic tests that we can run off the bat,

and you could customize this,

add to it, take away from it as much as you’d like.

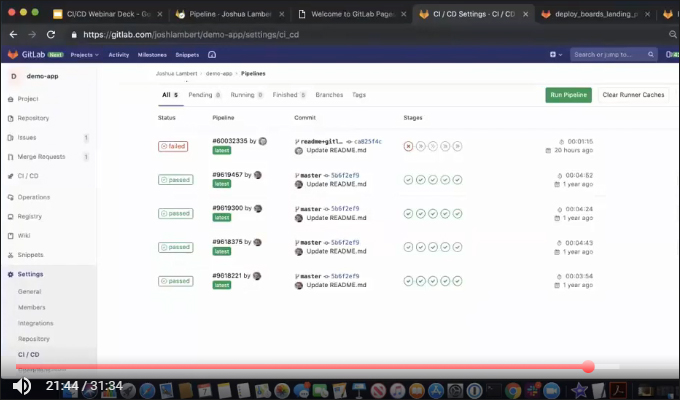

Now what I want to do is I want to take a

look at a previously random pipeline for

the YAML file that we just walked through,

so we’ll dive in here, and this is a graphical view of our pipeline

I’m going to jump into the unit test and

look at the build log as it was executed by a runner.

We could see here how Maven is executing

and finally how our tests have passed,

so the artifact from that is

displayed in an output of the test itself,

and we have a way to both download and

browse our job artifacts.

Over here is our code coverage, we will be able

to download and browse those job artifacts

and additionally these could

be accessed in the future by

other jobs as we’ve seen through our

pages functionality.

All that right there easily accessible let’s go over to

actually there’s just it.

I wonder… I was on the wrong one…

Pardon, got those mixed up. This was…

That was a Code Climate I was looking at,

I just scrolled him too fast there…

In the Code Climate…

done this too much that I was looking at it

In our code climate image… we can see… didn’t always go in there…

So in our

Code Climate… we could see that …

The Code Climate image was executed within

in the dark lines, so we

collected the output from that job

and again that’s persists as an artifact,

which is also available as downloading and

browsing here on the side,

on the right side. But what I want to do is hop

into our deploy stage and then hop into

our deploy job,

and now be able to see

that we were able to

publish our library to our package cloud

server usually utilizing Maven.

So if you remember earlier that we utilize a protected variable

and with that protected variable this was to ensure

that the secure token was not committed

to the repository and we could see right

here I’m where I highlighted one that

that’s referencing variable without

actually displaying token

in the log itself. So now our

library is available for others to consume.

I jump into the pages job.

It’s just running these bash commands putting

the files that we want to save

in a unified folder again and

persisting those artifacts. That is is

our pages functionality, and then it

displays those as that aesthetic website

that I just showed earlier right here.

So this is what this pages job is doing,

giving us this information about code

quality or docs of our code coverage.

Something to know about GitLab is,

that GitLab provides a number of ways

for notifications, to know either it’s

successful or unsuccessful run.

You can get it in browser notifications,

if you have Mattermost or Slack (note Slack setup),

you can integrate that with GitLab

and get notifications via those two

or you can receive email notifications

on passed or failed pipelines, probably

failed pipelines more often than not.

I’m top right here, you can see the favicon

showing that it has passed.

If it has failed you’d have a red X showing as well.

Going back to our pipeline view.

We see now how our cross-project pipeline

worked for our our front-end service.

So we see all these green checkmarks,

which great and then our trigger

which fires off our downstream

pipeline, and then what we’re able to do

is if I go over here to this other

project, demo-app, I can go on to that

pipeline, which I did here.

See that this pipeline was triggered from our upstream

project and that our build, test, package,

deploy and run stages all completed

successfully, showing that our upstream

changes didn’t affect our downstream

product maliciously.

Obviously, this kind of cross project pipeline

trigger is great if you’re having a

micro service project that has multiple

projects that makes up a a larger

project itself.

Additionally GitLab has a built-in

container registry so if you have any

custom images that you want to

store in GitLab either for better

performance or you just don’t want them

display it on Docker Hub, you can store

those all within GitLab.

We do have one container here and

I could want to click into it.

I can either manually prune these if I want,

and of course like GitLab does everywhere,

there is instructions on using our

built-in container registry on here as well.

So that’s a CI pipeline and with a few lines of YAML, we’ve basically have accomplished

an integration with Maven

with our units test, our code coverage and

Code Climate; we generate some

documentation, we published our library

to package cloud, we generated some so we

will publish the latest

documentation to our pages website,

trigger downstream project pipeline.

That’s to ensure that there are no negative

impacts, and we can do all of that

without involving a single administrator

opening up a ticket, and this was

completely self-service by me

the developer, with no plugins needed.

Now at the beginning of this demo I

mentioned that there are two parts to

GitLab CI/CD, and and we’ve spent a lot

of this time here looking at the CI YAML file.

And so take a quick look

over at the GitLab runner, and we’ll

talk about a few minutes basically

about how this is important part

of GitLab CI/CD.

GitLab runner is a small portable app, you know, which

we build for a wide variety of platforms.

It’s essentially the worker bee,

it picks up and executes the jobs

that we specified in our pipelines.

In our CI/CD settings here this is where a

developer can take a look at the

runner configuration for their

projects, so you’ll see that we have, as we

talked about earlier, two categories of runners, shared and specific.

Shared runners are runners

that have been provided by

administration of the GitLab instance,

so we’ve been using several or one here.

A couple different shared runners as you

can see, and what this does is by

allowing administrators to provide a

shared pool. There are a number of

benefits, and those could be consolidation

of infrastructure, whether it’s cloud or on-premise.

Clusters and credentials can be centrally managed,

it can reduce efforts required to set up CI

for each team, but there are some cases

where an administrator has maybe not

provided a shared pool or they don’t

meet your needs and for these cases we

have the ability for for any dev team to

connect their own runners. They simply

download the runner, enter the URL and key

and you’re just on your way.

And I mean to show how simple that is.

I’ll just show the process real quick here

but in the interest of time I did

install the GitLab runner,

so if I were…. I get this thing wait…

I’ll just get, I’ve run register, it’s

gonna ask for your URL, everything’s

provided here, I can simply copy that and

then paste it, and then same thing with the token.

Not too much difficulty around that…

Do a description.

And then it’s gonna ask you if

there are any tags that we want to specify.

So like we talked about, tags allow

you to uniquely identify runners

with certain properties. Maybe in this case

you know, as we’re

working on mobile applications

and I’m working on iOS,

I’m just gonna give it that tag

to identify specifically what I’ve

installed with that tag,

and that could be specified in the .gitlab-ci.yml file

that we went through for the job

that we want to run.

Last choice what we

have is what mode of operation we

we want for a runner.

So simple C shell

executes the script on the machine in

the account that is installed on.

We then have support for working with images and

containers via VirtualBox, Parallels,

of course Docker, and Kubernetes.

The runner will start the specified image,

execute the job and then clean up.

These modes are great for shared runners

because the development team can bring

their own base image to start from.

Our last mode of operation is what we call

our autoscaling runner. We support this

on Docker machine and Kubernetes and

and here this is when the runner will

elastically process jobs as needed

to process the CI queue.

I’m just gonna do “shell”

Registered successfully and

refresh the page, click on runners, and there we are,

and my runner up and ready to go.

In that case pretty simple but it’ll

take a little bit of time here…

We’ve got two of them… Oh, deleted the other one earlier someone else’s.

It’s gonna do a couple minutes of back and forth and

then it’s gonna have a green.

I did it in this project and I’ll have a green

available ready to go.

I’m not gonna do any building beyond that,

but I did want to talk on Canary

deployments. I don’t have it set up for

this demo but talking about Canary

deployments, when people are

looking to embrace continuous delivery,

company often needs to decide what type

of deployment strategy to use. One of the

more popular strategies is Canary

deployments, where a small portion of the

fleet is updated to the newest version first.

This subset then can serve

as a proverbial canary in the coal mine,

and if there’s a problem with a new

version of application, only a small

percentage of those users are affected

and the change can either be fixed or

quickly reverted. So if you’re leveraging

Kubernetes Canary deployments,

you can visualize your Canary deployments

right inside your deploy board,

and you don’t even have to leave GitLab to do that,

and I just want to show this is in a different demo,

but only showing one here,

a nice image to show that, and our

the deploy board is here and we could see

several different instances that

have been set up, so our Canary deployments

can be used when you want to

ship features to only a portion of your

pods fleet and watch the behavior as a

percentage of your user base visits the

temporary deployed feature.

If all works well you can deploy the feature to production.

I’m knowing that it won’t cause any problems.

Canary deployments,

you know, a lot of times they’re

very very useful just for like backend refactors

or performance improvements,

maybe other changes where the user

interface doesn’t change but you want to

make sure performance stays the same or improves.

So this is the ability of GitLab CI.

It’s to allow development teams to set up

their own CI/CD infrastructure.

It’s very very transformative.

A couple of points: first is self service

instead of needing to file a request for

a new piece of hardware, the wait for the

response, justify the changes cost and

have a PO potentially filed, dev team

takes two minutes with an old machine

from maybe from the cabinet and they off

they go. Dev team is happy and more

productive. Infrastructure team is happy,

they don’t have to worry about managing

maybe a flock of what Mac minis for iOS

team in their data center.

Second, it’s going to provide a lot of flexibility.

So if you need to run jobs

in IRM device perhaps, or Android, or deep

learning, it’s easy.

It’s easy as installing just the runner on Android.

Need to run something you know like on a

mainframe, like ?, just build

the runner, the way you go. If we

don’t support any operating systems, the

SSH executors that can login and and run

bash commands, so managing hardware and

software when something like a

container is not possible, it’s pretty easy.

Scalability: You know, with

a handful of auto-scaling runners on gitlab.com,

they routinely processing over thousand

concurrently fifteen hundred or more CI

jobs, and if more needed just simply turn dial.

So GitLab CI/CD and

you know there’s a lot to GitLab, and

I try to shove a lot

of it in the time frame, there’s more that.

We’re hoping to keep doing more webinars,

more technical deep dive and specific webinars or just videos that

we’ll post out to

YouTube, but GitLab CI, it’s

very very flexible.

If you bash it, now you can

automate it in the YAML file, you have

you know self-service runners and no

external plugins to manage and maintain.

You don’t have a brittle

configuration, and you have SaaS QA LTI

with auto scaling runners, if you

want those available to you.